I suppose it seemed like a good idea in the beginning. There were three serious contestants, and a $50,000 first place prize. But in retrospect, it should have been obvious that nobody was going to collect a dime of that money. It was 1911; flying was still brand new and the world’s first two pilots - Wilbur and Orville Wright - were still learning how to fly.

The world's third pilot was U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge. He died (above) on 17 September, 1908.

In that same crash Orville Wright was also badly injured. He would never fly again.

The second famous pilot to die in that first generation of pilots, in 1910, was Charles Stewart Rolls (of Rolls-Royce fame) (above). Considering there were only about 100 men (and one woman) with flying licenses in America in 1911, two percent was an appalling death rate, bad enough to make you wonder why anybody would have wanted to even try flying - let alone try flying from coast to coast across the United States.

The world’s 49th licensed pilot was a shy, cocky, 6’4” thirty-something, cigar smoking, playboy and adrenaline junkie with a hearing loss and a speech impediment named Calbraith Perry Rogers (above -right). He was a romantic who favored action over words, as proven by the way he met his wife, 20 something Mabel Groves (above, left). He saw her slip off a dock and fall into the water. So assuming she was drowning, he jumped in and pulled her to safety. Within a few months he married her, despite the hat. Cal approached flying with the same spontaneity as his love life, but it was a passion which quickly developed into a mission..

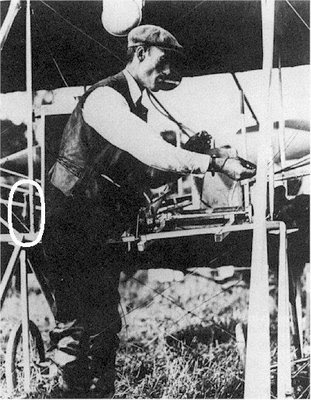

Having seen his first airplane on a visit to Dayton, Ohio, in June of 1911, Cal took the full Wright Brother’s flight course (above), all 90 minutes of it. Mabel explained that flying filled the hole in his life left by his deafness which had excluded a military career. It was, she said "the last piece of a jigsaw puzzle".

Then Cal talked his mother, Maria, into loaning him $5,000 so he could buy a Wright Model B Flyer “E-X”. The "X" was for experimental – which was a joke because in 1911 every “airplane” was experimental. But Cal may also have been the origin of the phrase to “take a flyer”, because just two months later, in August, he entered his new Wright Flyer in an air show in Chicago and took home third prize, worth $11, 285. Not bad: Cal had been a pilot for 60 days and already he had made six grand profit. He suspected there might be money in this flying thing.

And this was confirmed in October of 1910 when the Hearst newspaper chain had offered $50,000 to the first pilot to make it across the continent in 30 days or less. The offer was set to expire on 10 October, 1911. Orville Wright tried to warn Cal. "There isn't a machine in existence that can be relied upon for 1,000 miles, and here you want to go over 4,000. It will vibrate itself to death before you get to Chicago." But Cal refused to give up the idea. He explained, "It's important because everything else I've done was unimportant." Faced with that level of stubbornness, Orville tried to look at the bright side. At least the Wright B Flyer was so light, said Orville "six good men could carry it across the country."

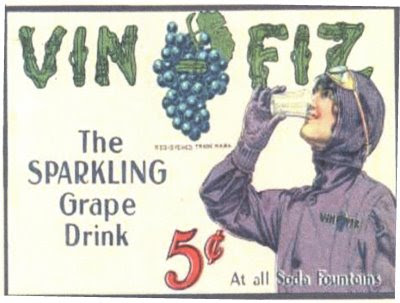

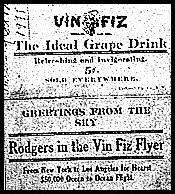

What Cal needed, as any NASCAR driver can tell you, was a sponsor. He found his ‘sticker sucker’ in Mr. J. Odgen Armour, owner of Armour Meat Packing Company, and his new soft drink called “VIN FIZ”. Allegedly it was grape favored soda water, but one critic thought it tasted more like “a fine blend of river sludge and horse slop” With a product like that Mr. Amour was going to need a heck of an advertising campaign. Enter Cal and his flying bill board.

With a guarantee of $23,000 from Amour, and a bonus of $5 per mile east of the Mississippi River, and $4 per mile to the west of the "big muddy", and a corporate three rail car support train complete with a reservoir of spare parts, fuel and mechanics, and sleeping car accommodations for Mable, Cal’s mother Maria, his cousin, his head mechanic Charlie Taylor, two other mechanics, two general assistants and assorted reporters from the Hearst news service, the flight was starting to look possible.

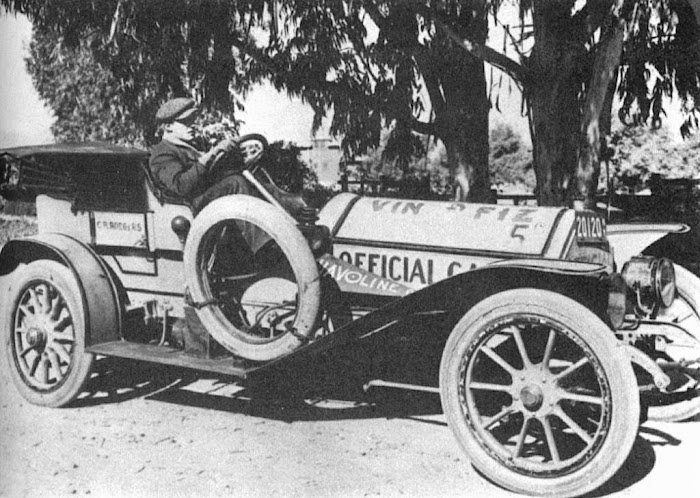

Armour even threw in an automobile (above) to track down Cal whenever he crash landed . With that much corporate funding behind him, Cal figured he had it all figured out. The first problem was that, before Cal even got airborne, his "Vin Fiz" was already in third place.

First off, from Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, was motorcycle racer Bob Fowler (above).

There were 10,000 cheering people there at 1:35 P.M., on Monday, 11 September, 1911 to see Bob takeoff (above).

Like Cal, Bob was piloting a Wright “B” Flyer, except his sponsor was Joseph J. Cole (above, middle, with mustache) , founder and owner of the Cole Motor Company, of Indianapolis, Indiana. Cole supplied Bob with his automobile engines and $7,500 in financial support.

The Cole engine was more powerful than the Wright engine, but it was also 200 lbs heavier. J.J. also gave Bob a support train, with spare parts. His mother, Ethel Fowler (above), went along and repaired the fabric of his plane during the flight. But "The Cole Flyer" lacked the publicity Hearst supplied to support the "Vin Fizz Flyer".

Making an average speed of about 55 miles an hour, Bob reached Sacramento in just under 2 hours, and after schmoozing with California Governor Hiram Johnson, Bob flew on to the foothill town of Auburn, for a total distance on the first day of 126 miles. Impressive. And on a Monday.

On Tuesday, 12 September, Bob had reached Alta, California, where he crashed into some trees. Bob was now out of the race until repairs could be made.

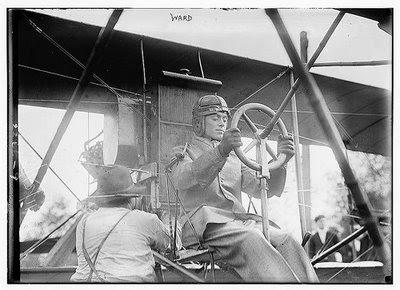

Second to start was James J. (Jimmy) Ward (above), pilot's license #52, and previously a jockey, and another motorcycle racer.

Jimmy was flying a Curtis Model D. and he had the full support of designer Glenn Curtiss, including the de rigueur train with a hanger car filled with spare parts,

Traveling with Jimmy was his second wife, Maude May Mauger - seen here strapped in for her first (and only) flight, with her husband at the controls.

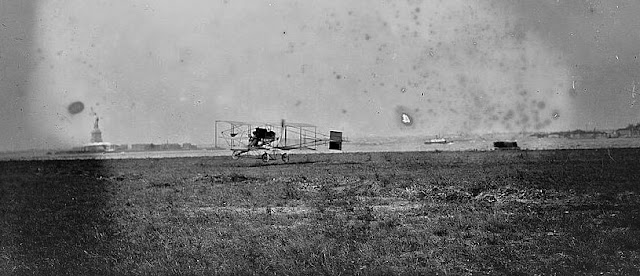

Jimmy took off from Governor’s Island in New York harbor on Wednesday, 13 September, 1911. He preformed a loop around the Statue of Liberty (above left, BG) and then immediately got lost over New Jersey.

He made only twenty miles before crash landing (above). Then he too had to wait for repairs. The basic tempo of the race had thus been set right from the start; take off, crash, wait for repairs, take off, crash, wait for repairs, and repeat as necessary for 4,000 miles. It was going to be very hard to finish this race, let alone win it.

Before starting himself, Cal Rogers tied a bottle Vin Fiz to one of his wing struts (white circle on the left), “for luck”. For reality, he tied a pair of crutches to another strut, in case he needed them later. He would.

Before a paying crowd of 2,000, a chorus girl poured a bottle of grape soda over the landing skids and proclaimed, “I dub thee “Vin Fiz Flyer””. Cal actually called his plane “Betsy” but he recognized the value of naming fees even back then.

Cal took off from the race course at Sheepshead Bay, Long Island at 4:30 p.m. on Sunday, 17 September. And if anybody noticed that it was the third anniversary of the crash that had killed Lieutenant Selfridge, they were polite enough to keep it to themselves.

After take off, Cal buzzed Coney Island and dropped coupons for free Vin Fiz soda (above). Then as the breathless reporters breathlessly reported, he flew over Manhattan “…with its death-trap of tall buildings, ragged roofs and narrow streets”. Cal landed safely in Middleton, New York that night to a cheering crowd reported as 10,000 – not to be bettered by San Francisco. He had made all of 84 miles that first day. His plan was to average 250 miles a day.

That night the reporters wrote that Cal claimed he would be in Chicago in four days. But Cal rarely talked to reporters because he barely heard their questions, the byproduct of a scarlet fever attack in his childhood. And he spoke in the clumsy monotone of someone who never clearly heard a human voice. So it was easier if the the reporters just made up heroic quotes for Cal. And they did.

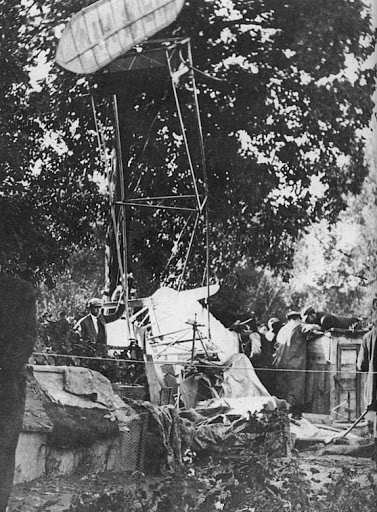

They invented more heroic quotes for him the next morning when, on take off, the "Vin Fiz" hit a tree and ended up in a chicken coop (above). The bottle of Vin Fiz was "miraculously" undamaged, as proved because it would have been impossible to find another bottle of Vin Fizz aboard a train car named "The Vin Fiz Special". But now it was Cal’s turn to wait for repairs. The race was on! It just wasn't going anywhere very quickly.

- 30 -