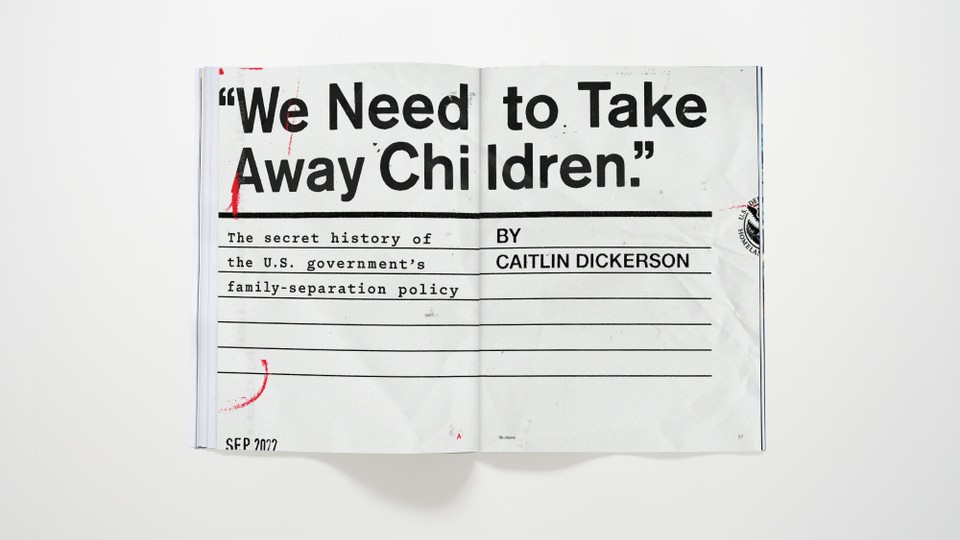

“We Need to Take Away Children”

In the September issue, Caitlin Dickerson wrote about the U.S. government’s family-separation policy.

What a superb piece of investigative journalism by Caitlin Dickerson. I hope the detailed history of this sordid story leads readers and voters to be more diligent about watching the way governments, both state and federal, deal with immigration.

Ron Kochman

Kenilworth, Ill.

Caitlin Dickerson’s breathtaking investigation exposed the malice and incompetence of the Trump administration, as well as the failure of hundreds of government officials to stop a policy that deliberately traumatized thousands of children and parents. It reaffirms why Physicians for Human Rights concluded in 2020 that family separation meets the United Nations’ criteria for torture and enforced disappearance.

As outlined in the UN’s Convention Against Torture—which the United States ratified in 1994—four elements must be met to legally define acts as torture. Torture (1) causes severe physical or mental pain or suffering; (2) is done intentionally, (3) for the purpose of coercion, punishment, or intimidation; and (4) is conducted by a state official or with state consent or acquiescence. Both Dickerson’s investigation and PHR’s reports on the health consequences of family separation show that all four criteria for torture were met. The trauma from these separations did not disappear when families were finally reunited. As a perpetrator of state torture, the U.S. government is obligated to provide prompt and effective redress to survivors, including psychological rehabilitative services. Despite calling family separation “criminal” on the campaign trail, Joe Biden has done little for its survivors. Instead, his administration’s Department of Justice is fighting these families in court and defending the abhorrent family-separation policies of the Trump administration.

Thank you to The Atlantic for keeping this issue in the public spotlight. The officials who devised family separation or who stood by while this abuse was perpetrated may wish to turn the page and move on, but the thousands of families who were separated cannot do so until the U.S. government acknowledges the harm it inflicted and provides redress.

Ranit Mishori

Senior Medical Adviser, Physicians for Human Rights

Washington, D.C.

As a state child-protection caseworker for 30 years and, more simply, as a human being, I was horrified when I first heard of Donald Trump’s family-separation policy several years ago. Caitlin Dickerson’s putting names and faces to that policy gave it a more poignant and personal horror.

I grieve for the America that these leaders are carving out for my children and grandchildren. I feel anger and disgust at the moral bankruptcy and incompetence of the Trump world, and I was brought to outrage and despair by the report that border agents mocked immigrants. How can one possibly conceive of ripping a baby from a mother’s breast while chanting “Have a happy Mother’s Day”? Is this the face of America? May God help us all!

Fred Putnam

Houlton, Maine

I could read only a page or two at a time of Caitlin Dickerson’s article. The pain of the families being ripped apart was palpable. Reunification will be merely the first step; healing the rupture of trust will take far longer. Studies of trauma indicate that this pain and its consequences may be passed on for generations. We, the people of the United States, allowed our government to do this. We should hang our heads in shame.

We can’t heal the immigrants’ trauma or mend the hearts of the perpetrators. What we must do is update and restructure our immigration system, now.

Judith Matson

Vista, Calif.

Let Brooklyn Be Loud

The sound of gentrification is silence, Xochitl Gonzalez wrote in the September issue.

Reading Xochitl Gonzalez’s description of the “aesthetic” of silence, I realized that it was one I grew up with, was trained to revere and need. I consider noise—whether from a stereo, a car horn, an argument, a racing motorcycle, or a party—an intrusion, a violation of my space and contentment. Why the need for so much quiet? What joy and life does this need snuff out in others and in myself?

I’m not sure I’ll succeed, but the next time I’m bothered by another’s shouting, I’ll try to remind myself that life is a loud affair. It was always meant to be, from a baby’s first cry.

Jean Cheney

Salt Lake City, Utah

I love quiet. I’m currently in a protracted struggle with my local city council to have high-powered leaf blowers banned. They are an incredible nuisance, disrupting not only every sleeping child and working neighbor for a 10-block radius, but also every bird and bee.

Yet I fully agree with the author that we should let our neighbors speak, laugh, cry as loud as they wish—and, yes, even party. I do not want to live in a world subsumed by machine noise, but I most definitely want to hear the sound of people living their lives fully.

I believe that my local city council’s exemption of leaf blowers from our local noise ordinance is racist, or at a minimum classist. Consider, for instance, a lively gathering of people of color being reported for a noise violation and the cops showing up. In contrast, my rich white neighbor can rest at ease knowing that their high-powered leaf blowers remain exempt. The implicit statement is that your party, your friends, your life are less important than your neighbor’s manicured lawn.

Elliot Cohen

Boulder, Colo.

Behind the Cover

In this month’s cover story (“Good Luck, Mr. Rice”), Jake Tapper writes about C. J. Rice, who was sentenced to decades in prison as a teenager and whose experiences reveal the empty promise of the constitutional right to counsel. For the cover, we commissioned the artist Fulton Leroy Washington, known as MR WASH, to paint a portrait of Rice. Washington recognized much of his own story in Rice’s—he spent 21 years in prison for nonviolent drug convictions before having his sentence commuted in 2016 by President Barack Obama. “I realized that C.J. and I were similarly situated,” Washington told me. “He’s on a journey, on a path, that I have been blessed to make it all the way through.”

As a child in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, Washington cultivated an interest in art through jigsaw puzzles. “We’d sit at the dining-room table, the family looking through the box and trying to find the piece that fits,” he recalled. “I would see the art coming together.” But he truly started honing his craft during his trial, to pass the time. “In the courtroom, I would draw butterflies and characters, and even little people, in pencil.”

[Read: An interview with Fulton Leroy Washington about the November issue cover art]

After his conviction in 1997—a life sentence without parole—Washington began experimenting with oil paints in prison. He focused on the human form, developing his signature style—photorealistic subjects with large tears featuring smaller portraits within. “I did a thousand eyes on one canvas, a whole bunch of noses, ears from all angles, a whole bunch of smiles,” he said. He continued to create over the course of his incarceration, eventually painting the scene that he believes freed him, a prophetic work titled Emancipation Proclamation. In the painting, which depicts then-President Obama signing Washington’s clemency papers, the artist reimagines Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln. Two years later, life imitated art, and Washington was freed. He is working on several exhibitions and setting up his new studio in Compton, California.

Oliver Munday, Associate Creative Director

This article appears in the November 2022 print edition with the headline “The Commons.”