When describing their symptoms, medical history and health changes at a clinic or hospital, every patient is the storyteller of their own health. Good storytellers tend to get better health care, but a history of childhood trauma plays havoc with telling your own story.

Consider Florence, as a (fictional) example:

It is a hot July night and Florence is having dizzy spells again. She feels dreadful and is worried. What if it happens when she is driving? What if it doesn’t get better? How can she work like this? What if it is a stroke or a tumour? She goes to the emergency department in spite of her past experience that it isn’t very helpful.

The triage nurse asks what she is there for. “Well, I had this bad thing… they did tests and it was almost normal…”

The nurse looks puzzled. “When was that?”

“October. I was…” The triage nurse doesn’t need to hear what happened nine months ago. She cuts Florence off and points her toward the waiting area.

A while later Florence meets with a doctor. She has been practising what to say while she waits. He interrupts after a few seconds to ask what Florence means she by “dizzy.”

Florence replies, “You know, it’s like that dizzy feeling, oh I hate that, you know …”

Although it doesn’t occur to either Florence or the doctor, a lifetime of difficulty — starting with violence that she witnessed and experienced as a child — is compromising Florence’s health.

ACEs and health

Research on the links between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and poor mental and physical health has made this formerly hidden risk factor for many of our most common and burdensome chronic diseases a topic of public discussion.

The numbers are mind-boggling. About 60 per cent of adults experienced at least one type of ACE as they are usually defined. About one in three children experience serious physical or sexual abuse or are exposed to interpersonal violence. It is a major public health problem.

ACEs are linked to unhealthy behaviour and experiences later in life. They increase the risk that a child will smoke cigarettes, adopt unhealthy drug and alcohol use, become obese, or experience further trauma as an adult. Because of this, and because of other effects of stress on health, ACEs increase the risk of diseases of the heart, lungs and liver, pain syndromes, and some cancers.

What Florence is experiencing in the emergency room is a further consequence of childhood adversity — one that makes it much harder to get good health care. There is a strong relationship between unresolved developmental trauma and impaired storytelling. This is technically called “narrative incoherence.”

Storytelling and health

The qualities of a good narrative were described by the philosopher Paul Grice in four maxims:

- have evidence for what you say (quality),

- be succinct, yet complete (quantity),

- be relevant to the topic at hand (relation) and

- be clear and orderly (manner).

Psychologist Mary Main and her collaborators used Grice’s maxims to describe how unresolved childhood trauma and loss can affect a person’s state of mind regarding important relationships in their life. They found people with unresolved trauma could be identified by failures in the quality, quantity, relation and manner of the stories they told during an emotionally taxing interview about those relationships.

It is a short leap from that research to high-stakes conversations in an emergency department or doctor’s office where someone like Florence struggles to make her condition clear and receive the help they need.

Styles of narrative incoherence

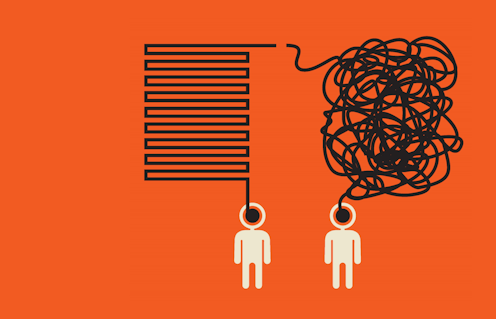

There are two common patterns of incoherence in these interactions. Florence’s pattern is called preoccupied. Her anxiety is obvious. She is too overwhelmed by fear to organize her thoughts. She presents events out of sequence; her thoughts are unfinished; there are too many details; it is hard to tell the signal from the noise.

As a result, it can seem like the story of Florence’s health is a jigsaw puzzle and all the pieces have been dumped on the table at once. A listener feels baffled and frustrated. The doctor may start his note with the comment “poor historian.”

The second pattern of narrative incoherence is quite different from Florence’s preoccupied pattern of providing too much disorganzied information. A person with a dismissing pattern tends to provide conclusions without evidence, and generalizations without examples.

Q: “How does that feel?” A: “Same as always.”

Q: “How long has this been going on?” A: “A while.”

The conversation is short and at its end a health-care provider is unilluminated. While someone like Florence wears her anxiety on her sleeve, a person with the dismissing style keeps their cards close to their chest. A listener feels uninvited to ask more.

Practical steps

If Florence and her health-care providers are able to recognize that trouble telling her own story is a clue to what is going on — not just a marker that she is a “poor historian” — they can take steps to meet the challenge. Some steps Florence can take include:

- Bringing a friend with her who helps her stay calm and organized.

- Explaining that she is anxious and needs a little time to describe the trouble.

- Making notes in advance about her most important points and questions.

Even more importantly, health-care workers need to recognize the face of fear. The doctor can help Florence to organize her thoughts instead of interrupting to interrogate her. They can help each other to find the story that allows her dizziness to be understood.

Every patient is forced to be a storyteller; a health-care professional’s job is to make them an excellent one.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.