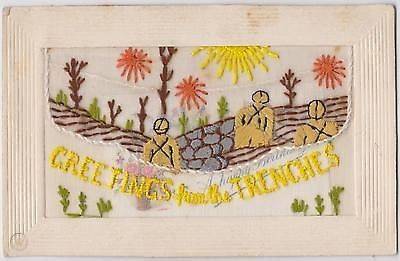

World War I was a brutal conflict, especially on the Western Front. Battlefield conditions there were horrific: “a chaotic, cratered hellscape,” as The Atlantic’s Alan Taylor described it in a 2014 retrospective, where soldiers in muddy trenches fought to survive an onslaught of bullets, bombs, mustard gas, bayonet charges, and more, including new technologies — machine guns, tanks, chemical and aerial warfare — that vastly increased killing power.

Yet the anxiously-awaited messages their loved ones received from the Front were often sent in the daintiest form imaginable: embroidered silk postcards that became treasured mementos, many of which outlived their senders.

First introduced at the 1900 World Fair in Paris, these delicate missives were used in France to send greetings even before the war. They consist of a plain blank postcard to which an embroidered piece of silk has been affixed, then framed by an embossed paper surround.

The postcards were sold in thin paper envelopes, but they were seldom sent through the post in those envelopes. Instead, they were mailed along with letters. For this reason, many are unwritten, with no marks on their back sides. An unused WWI-era postcard, embroidered with flowers and the message “TO MY DEAR FRIEND,” sold on eBay UK for $5.37 on March 7, 2014.

Some postcards, like the one above, had a flap as part of the silk insert, creating a pocket effect that allowed them to hold a small pre-printed card. This butterfly-bedecked postcard bore the message “LOVING THOUGHTS”; its apropos enclosure card stated, “I’m ever thinking of you.” It sold on eBay UK for $8.46 on October 5, 2014.

Other postcards were trimmed with ribbons or bows. Popular designs included colorful depictions of flowers, birds, and butterflies along with sentimental messages. This lot of three embroidered silk postcards sold on eBay for $12.50 on April 9, 2010.

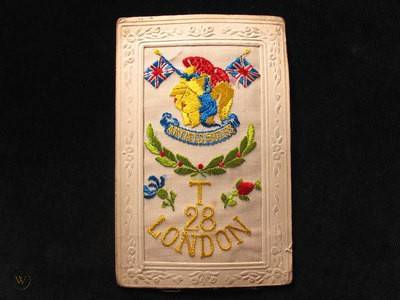

When war broke out in 1914, the beauty and uniqueness of these embroidered silk postal keepsakes made them wildly popular with soldiers from the Allied countries and, later, the United States. Timely new designs featured patriotic images such as flags, regimental insignia, and portraits of military leaders. A rare portrait of Lord Kitchener, complete with its original enclosure card, sold on eBay for $103.64 on October 7, 2012.

Even traditional flora and fauna got into the wartime spirit. A postcard bearing the embroidered message “FROM YOUR SOLDIER BOY” featured a butterfly whose wings are stitched with the flags of Great Britain, France, and Germany. It sold on eBay for $10.90 on July 30, 2013.

Some postcards rose to the level of wartime propaganda. One such card bears the title “The Iron Grip”; it depicts a clawed hand, its fingers and thumb each bearing the flag of an Allied Power, reaching down to grasp a matronly woman wearing an Iron Cross and carrying a sword, her jackbooted foot atop the upper rim of a globe. It sold on eBay UK for $139.25 on May 27, 2014.

Another military-themed postcard is stitched with a blue river containing the red-lettered proclamation “STOP NOBODY CAN PASS”. On one side of the river, the Union Jack is shown behind a British lion holding a key; from the other side of the river, a soldier takes aim. The top half of the silk insert is a flap that lifts to reveal an enclosed card printed with pansies along with the words “TO MY DEAR MOTHER”. This postcard sold on eBay UK for $93.17 on March 4, 2012.

Also popular were holiday and birthday greetings as well as dedications to mothers, fathers, sisters, wives, children, and sweethearts. A card embroidered with a trio of hens carrying a holiday feast along with the British flag next to the words A JOYFUL CHRISTMAS sold on eBay UK for $71.26 on September 25, 2012.

For those waiting at home, these fanciful messages from the front conveyed a much prettier picture than the grim reality of life in the trenches.

One lot of 12 embroidered silk postcards spans the gamut of the genre from peacetime through the war years. Some feature flowers and an enclosure card; others include flowers framing landscape vignettes along with the words “Souvenir de France.” One card wishes the recipient “Heureuses Pâques” (Happy Easter), while others bear more poignant messages: “Forget Me Not,” “God Be With You Until We Meet Again,” “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” “To My Dear Father from Your Loving Son,” “To My Sweetheart,” and “Yours Always.” This delightful dozen sold on eBay for $104 on October 12, 2014.

Comparable designs were also made with messages in German; these were sent home from the other side of the Front.

From 1914-1919, an estimated 10 million embroidered silk postcards were produced. More than 100 years later, an impressive number still exist — and they are surprisingly affordable, no doubt much to the dismay of those hoping to cash in on the contents of grandma’s scrapbooks. A quick look at eBay UK’s Collectable WW I Military Embroidered Silk Postcards 1914-1918 category shows nearly 1,500 listings, many priced at less than $20. WWI silks are scarcer on eBay.com, where they don’t have their own special category, but they can still be found at very reasonable prices.

A search of WorthPoint.com using keywords “silk postcard wwI” (without quotes) pulls up some 3,000 results, many of which sold for less than $20.

But particularly rare or desirable designs may sell for more. An embroidered silk postcard depicting the regimental badge of the T28 London Artists Rifles (an elite volunteers battalion) above a wreath of laurels sold on eBay UK for $377.71 on August 16, 2013. Embroidered silk postcards featuring regimental badges are among the most collectible and valuable examples of the genre.

Many sources would have you believe that these World War I silks, as they’re known, were hand-stitched by French and Belgian housewives and refugees, toiling away with a needle in their home or camp so as to eke out a meager income. It’s certainly a romantic backstory, and perhaps some WW I silks were indeed produced that way.

However, according to the Textile Research Centre (TRC) in Leiden, Netherlands, the embroidery was most likely done by commercial firms using machines that mimicked hand embroidery. These machines were capable of an amazingly wide range of stitches: back stitch, basket weave stitch, individual cross stitches, herringbone stitch, reverse herringbone stitch (in order to create a shadow-work effect), double running stitch (also known as the Holbein stitch), satin stitch, stem stitch, and various composite stitches.

This variety of stitches is shown to good effect on a fine collection of 20 WWI silks shown above that sold on eBay for $152.50 on January 25, 2016. Most bear the words “Souvenir of France” or “Souvenir de France”; one says “Souvenir of the Great War,” while others feature the dates of the war years (1914-1918). One is sweetly addressed “To My Dear Girl,” while another delivers “Kisses from France” and a third conveys “Christmas Greetings.”

To create the look of hand embroidery by machine, stitches were transferred via a hand-operated pantograph. Each stitch was drawn out on a large-scale version of the design; then its position was traced by the operator using a point on one arm of the pantograph. A series of needles responded to the movement of the pantograph. Each needle had two sharp ends, with an eye in the middle for the thread.

The needle was passed through the fabric backward and forward using a pincher system, thus imitating the action and appearance of hand embroidery. Each color in the design was individually stitched — for example, all the blue parts are worked at one time — and then the needle was threaded with a new color until the design was complete.

The TRC has in its collection long strips and large sheets of repeating designs. These designs were stitched onto silk gauze by the hand-embroidery machines, then cut out and glued onto cardstock. This made it possible to produce hundreds of images at a time — far more than could have been made by even the most industrious refugee women. The postcards were subsequently sold to the public (mainly foreign troops) at a relatively substantial price that probably resulted in a tidy profit for the manufacturer.

Says TRC’s Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, “Perhaps this is the real reason behind the stories of poor refugee women working all hours to hand embroider these cards in order to feed their desperate families.”

Once embroidered silk postcards were established as a popular (and lucrative) genre, several companies started making cards using truly mechanical embroidery machines, which did not imitate handwork. However, these postcards are not as well made as those produced on the hand-embroidery machines.

Embroidered silk postcards continued to be produced up until about 1956. They even enjoyed a brief resurgence of popularity in 1939-1940, when they were sent home by members of the Second British Expeditionary Force. These later examples tend to display more muted colors and a crimped edge on the card.

As to caring for these wartime relics, silk is a difficult material to preserve, because it is sensitive to light, handling, and humidity extremes and fluctuations. Close examination of many WWI silks will reveal some tearing of the silk and/or tiny holes developing.

In addition, the paper stock used during the First World War was often poor quality, so today it may show foxing (brown stains due to acid). This can sometimes be reduced by a specialist, but not always.

In most cases, the best way to preserve your WWI silk is in an archival sleeve inside a box or album. Never frame it for display; even if placed away from direct sunlight, it will quickly fade.

Want to find out more about these fragile stitches in wartime? Try these reference works:

- An Illustrated History of the Embroidered Silk Postcard by Dr. Ian Collins (2001; ISBN 0954023501)

- The Concise Catalogue of Embroidered Silk Postcards by John Westland (Suffolk Nostalgia, 1994; ISBN 0951836218)

Betsie “eBetsy” Bolger is a freelance writer/editor, former eBay Education Specialist, and Top Rated Seller on eBay. She sells new, estate, vintage, and artisan jewelry for a client’s account as well as Converse sneakers, vintage jigsaw puzzles, limited-edition Teddy the Dog merchandise, and select consignment items in partnership with her husband. Betsie is also a longtime WorthPoint fan who previously wrote WorthPoint’s commercial spots for eBay Radio. Find her via ebetsy.com, acquisatory.com, and TexAnnasAllStore.com.

WorthPoint—Discover Your Hidden Wealth®