It’s so exciting to turn a house into a home! I can’t wait to set up my eyeball-person sculpture in the living room and—wait, what do you mean you don’t like it?

What Is Décorum?

Décorum is a cooperative game for 2 to 4 players, ages 13 and up, and takes about 30–45 minutes to play. It retails for $44.95 and will be in stores on April 19; you can also order it directly from Floodgate Games. There is a deluxe edition priced at $49.95 that comes with acrylic tokens instead of cardboard. The game is sort of a logic puzzle, so although younger kids may be able to play it, the difficulty level scales up as you progress through the scenarios, and the limited communication rules mean make it difficult for parents to assist kids if they have trouble understanding their own condition cards.

Décorum was designed by Charlie Mackin, Harry Mackin, and Drew Tenenbaum, and published by Floodgate Games, with visual design by KOMBOH/Michael Mateyko.

Décorum Components

Here’s what comes in the game:

- Double-sided Roof board

- Double-sided House board

- Round marker

- 5 Heart-to-Heart tokens

- 4 Roommate tokens

- Object board

- 64 tokens:

- 16 Paint tokens (4 per color)

- 16 Wall Hanging tokens (4 per color)

- 16 Curio tokens (4 per color)

- 16 Lamp tokens (4 per color)

- 10 3-/4-player scenarios

- 20 2-player scenarios

- 4 divider boards

- 2 sealed packets

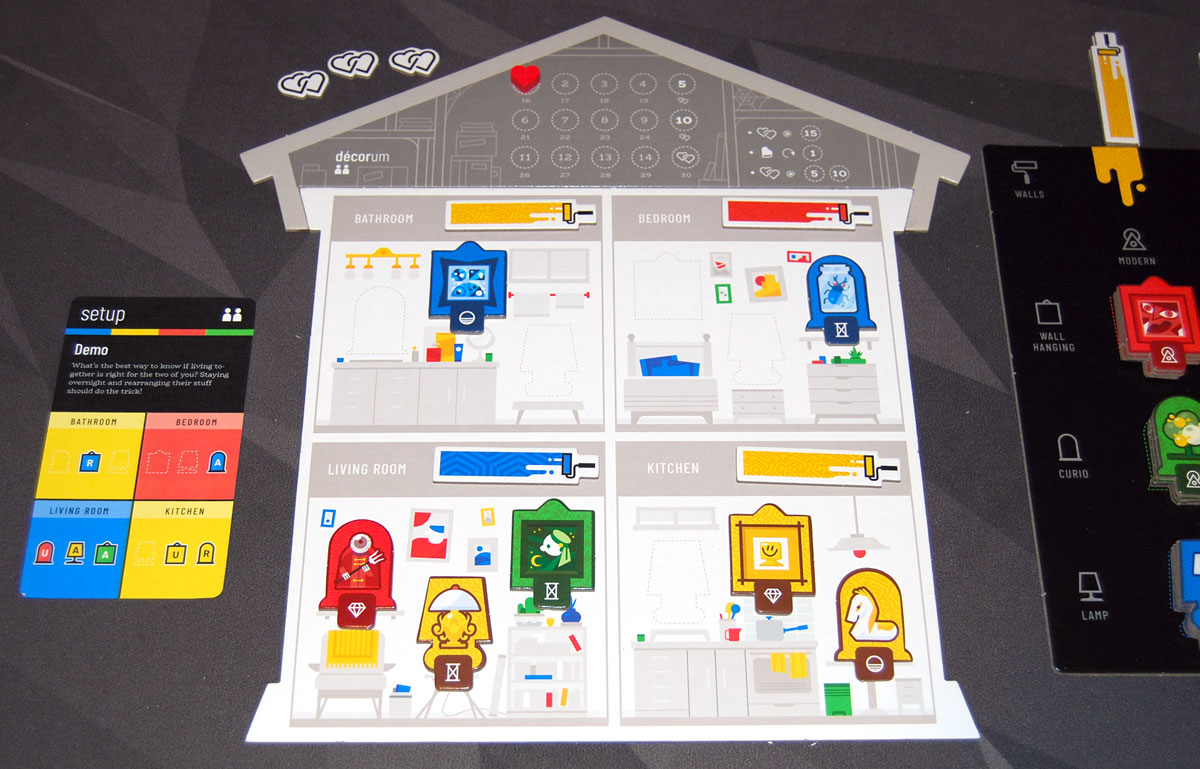

The house has a clean, minimalist look to it, mostly white with just a few bits of color here and there. That’s important because you’ll be filling it up with various objects, and it’s important to be able to tell at a glance what’s in each room. The objects themselves are wonderfully illustrated: aside from the four color options and three object types, there are also four styles—antique, modern, retro, and unusual. So you get antique curious like the jars of specimens, and unusual curios (my personal favorite) that depict weird eyeball-people holding silverware.

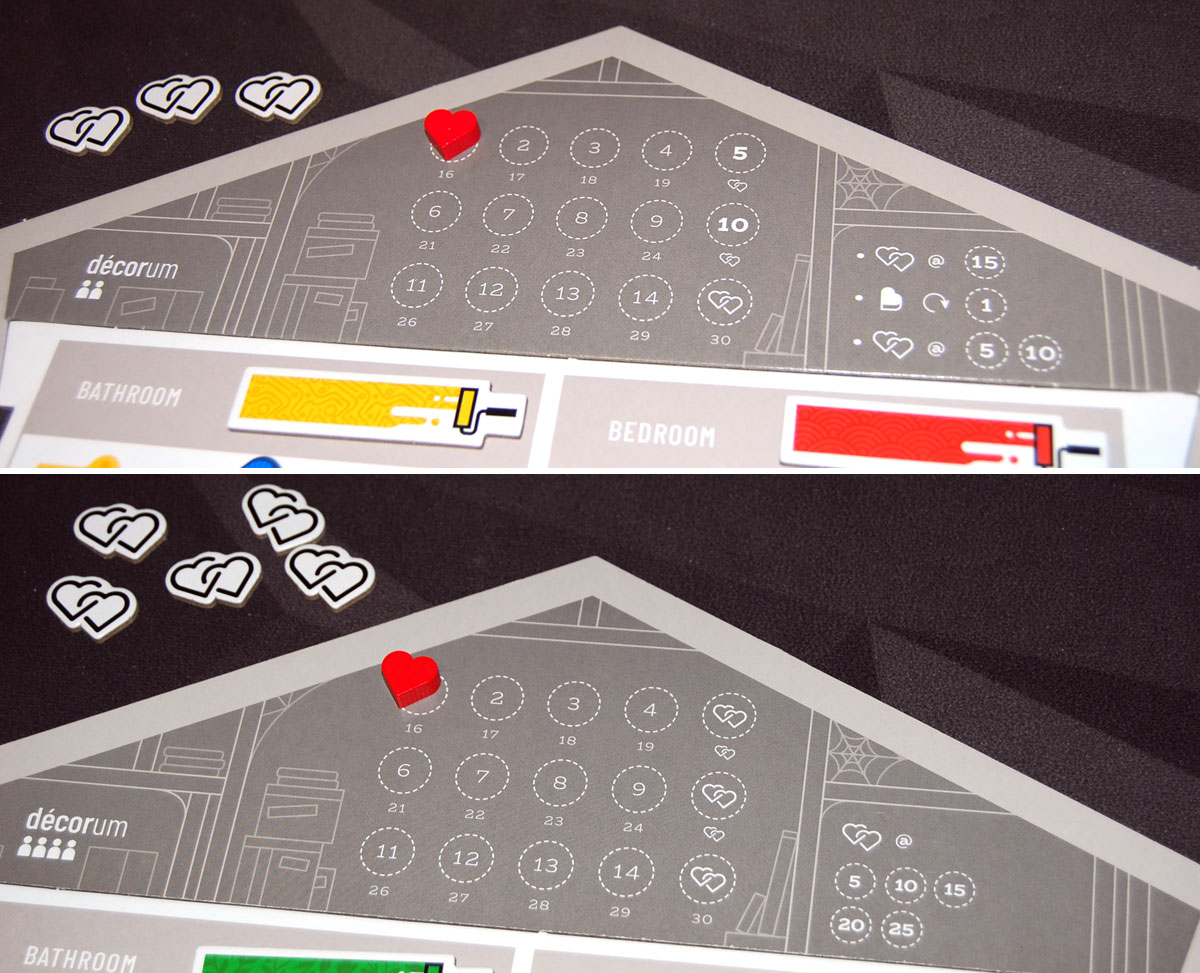

The roof board attaches to the top of the house and has a round tracker on it; it is double-sided, with one side for 2 players and the other used for 3- or 4-player games. The track goes from 1 to 15, with the numbers 16 to 30 printed below it, because you go through the track twice. There’s iconography on the right side that is intended to show when to have the heart-to-heart conversations, though I found it a little confusing at first and I feel like the 2-player side, in particular, is kind of odd, though once you learn the game you probably won’t need to refer to it.

The house itself is also double-sided: some of the 3- and 4-player scenarios will use the backside of the board, which has two bedrooms upstairs instead of a bedroom and a bathroom. The downstairs always contains a living room and a kitchen. Each room has a space for the wall color and one of each object type.

Each scenario packet contains a setup card and one large condition card per player—these are tarot-sized cards. In the 3-/4-player scenarios, each player will also have three small condition cards—these are used to share information. More on that later.

The two sealed packets are used in the 2-player campaign, which is intended to be played in order. You open one at scenario 12, and the other at scenario 15—they’ll add some new components and rules to the game. I’ve only opened the first packet so far, but I was a bit disappointed in how much wasted cardboard there was, and am not sure why this wasn’t simply a small envelope instead. The cardboard dividers are apparently used so that you can keep track of your progress in the campaign (maybe multiple pairs of players can track their progress?) but the rulebook does not actually explain them. In fact, the rulebook doesn’t even have a components list.

The rulebook is unusually bland-looking, at least on the outside: the front cover is a quickstart guide, and the back cover is a glossary, so when you first pick it up it looks like it’s missing a cover. It is handy to have those on the outside where you don’t have to search for them, but it is really strange to have a rulebook whose front cover is entirely text with no illustrations and only a very tiny hint of color. The rulebook itself is okay for the most part, but there are some things that feel not quite complete. For instance, there’s an explanation of how to tally up your score at the end of a game, but there’s no indication in the rulebook that each scenario could have a different potential maximum score, and there isn’t any sort of guide about what a “good” score is.

I’ve noticed a few errors on the cards—for instance, in the 2-player scenario 12 cards are labeled “1” instead of “12” for some reason. And there are some conditions where the wording itself is confusing and I think should have been made less ambiguous.

The game box has a mediocre plastic insert: there are wells for the scenario cards, and then three square wells for everything else. Setup involves separating out all of the object and paint tokens, so you really don’t want them all jumbled together, but the box doesn’t provide a good way to keep them organized. I guess you could bag things up separately, but what I do is stack things very carefully and then try not to jostle the box—but if anyone ever turned over the box to read the back, it would be a mess.

How to Play Décorum

You can download a copy of the rulebook here.

The Goal

The goal of the game is to arrange the objects and paint colors in the house so that everyone’s personal conditions are met.

Setup

To set up, you open a scenario envelope and find the setup card (being careful not to reveal any of the condition cards!). The setup card has a little story on it that sets the scene, and then a diagram of the house: place all the paint tokens and object tokens into the rooms as shown on the house. In some 3-/4-player scenarios, the roommate tokens will be placed into the bedrooms as well.

Place the remaining tokens on the token board, organized by color and type.

Give each player a condition card. The 2-player cards also have named characters, with a little bit of dialogue at the bottom that you can read aloud to introduce your character. In the 3-/4-player game, each player also receives the small condition cards that match their player color. (And in a 3-player game, the 4th player’s small cards are distributed as indicated on the card backs.)

Place the round marker on round 1, and set aside the heart-to-heart tokens (3 in a 2-player game, and 5 otherwise).

Gameplay

Each round, all players will take one turn. On your turn, you get to make one change to the house, from one of the following options:

- Change the wall color of a room.

- Swap an object for the same object but a different color.

- Add an object to an empty space.

- Remove an object from the house.

- Move your roommate token to the other bedroom, potentially displacing somebody there. (3-/4-player game only)

If you are fulfilled at the beginning of your turn, you may pass, but, otherwise, you must make a change.

After you make your change, you first announce whether or not you are fulfilled—that is, every condition on your card has been met. Then, the other players have a chance to respond, but they can only say “love it,” “hate it,” or “neutral.” (Or variations on those three themes—but you should try to avoid going into any detail, because that may give away information about your conditions.)

Every so often, there will be an opportunity for players to share information with others. In a 2-player game, it’s called a “heart-to-heart” and this happens at the ends of rounds 15, 20, and 25. Each player shares 1 condition with the other player. In a 3-/4-player game, it’s called a “house meeting” and happens every 5 rounds. Each player first gets to state how they’re feeling about the house overall and then shares 1 condition with 1 other player (using the small cards). You can’t share a small card somebody else gave you, but you can re-share one of your own small cards with a different player in future rounds. After these meetings, flip over one of the heart-to-heart tokens.

Game End

If at any point everyone is fulfilled, then the game ends and you win! If you reach the end of round 30 and you haven’t satisfied everyone, then you lose.

If you want to keep score, you get 3 points for every condition that was met, and 5 points for every heart-to-heart token remaining.

Why You Should Play Décorum

Playing Décorum feels like working on one of those logic puzzles, where Mr. Brown is seated next to Ms. White, and Perry has a pet dog, and Joan’s last name is Green, and the owner of the bird is seated next to the person who’s allergic to peanuts. There’s a solution to getting everything into the right place, and the goal is to figure it out before you run out of time. The difference, though, is that in this game each player has an incomplete set of clues. So while you’re trying to make sure that every room in the house has a red lamp, another player is trying to make sure that green is the most commonly used color in the kitchen.

Décorum‘s subtitle is “a game of passive-aggressive cohabitation,” and it really plays out like that. You remove a wall hanging, and your partner says “I hate it.” They paint the bathroom green, and you say “I hate it.” Everyone has needs they want met, but nobody comes out and says what they are—because shouldn’t you know what I like? Don’t you care about my needs? Why would you take out my favorite eyeball sculpture and replace it with an orrery? In practice, this means that you’re trying to figure out the balance of how to signal what you want and reading the signals from the other players so that you can all get what you want.

It gets tougher and tougher, though. In the easier scenarios, the conditions are simpler and you may be able to figure out why another player is upset at the change you made. You can try out hypotheses: “Okay, I’m putting this in and—oh, they love it! I think I’ve figured out one condition.” But as the game gets harder, there are some truly off-the-wall conditions that I would never have picked up on without being told, and so you really rely on those heart-to-hearts.

That in itself can be a tough decision: which condition do you share? And with more players, which player do you share it with? It’s not uncommon for one person to receive a whole lot of information, while another player gets no new information. It’s like having a house meeting and saying, “Look, Bob over there is the one who keeps messing things up, so everyone wants to have a word with Bob.”

One downside to the way the game works is that you can’t really ask for help if you don’t understand your conditions. Some conditions are really easy to understand, like “the kitchen must have a blue wall hanging.” But some have confusing wording: if it says “the kitchen and the bedroom must have equal numbers of red objects and equal numbers of blue objects,” does that mean you need the same number of both red and blue objects? Or the same number (x) of red objects in both rooms, and the same number (y) of blue objects in both rooms, but it’s okay if x and y aren’t the same? Over the course of the games, we’ve run into a handful of conditions that are worded in a way that allows for multiple interpretations—which can be frustrating when you can’t simply ask another player what it means, and the glossary only covers the most basic terminology.

One of the tricky aspects of the puzzle is that not every combination of color-style exists. For instance, if you need an antique object, your choices are the green wall hanging, the blue curio, or the yellow lamp. There is no red antique object. And if you want a yellow curio, then it’s retro and not antique. For many of the scenarios, knowing which color-style combinations are missing can be crucial to figure out where to start.

The 2-player scenarios are intended to be played in order. Not only do they get increasingly complex as you progress, but you’ll start to see characters from earlier scenarios return, which is a lot of fun. I’ve been playing through these with my 15-year-old daughter, and we both really enjoy reading the stories. Just as a preview, the first scenario has Blake, who loves everything about Spencer except his fondness for horror movies because Blake scares easily. Meanwhile, Spencer keeps forgetting to tell Blake that his mom’s ghost lives in his lamp. “Oh well, they’ll get along!” (Narrator: They did not.)

While the 3-/4-player scenarios have a little story on the setup card, the individual player cards don’t have character names or stories, which is too bad, because it adds a lot of fun flavor to it. Those come in 3 difficulty levels and can be played in any order (and are totally independent of the 2-player campaign).

I listed several nitpicky things in the components section, and there are definitely some conditions that I think were not phrased well, but overall I’m still a big fan of Décorum. My daughter, who plays a lot of games with me but generally at my request, has frequently been requesting more, and we’ll play a couple of the 2-player scenarios in one sitting. She even suggested it one afternoon to her older sister and a couple of friends—and this is a kid who is extremely introverted and never suggests activities!

I like the 2-player game for the developing stories, and I like the version with more players because of the added challenge of deciding who to share information with. The roommate tokens are mostly used in the more advanced scenarios, but I like the added complexity: which room should I be in? Which person is a compatible roommate based on our wants?

While we’ve had a pretty good track record for wins so far, there have been some real challenges. For some scenarios, it’s been a puzzle to figure out how to get everything to work even once we ran out of time and reveal everyone’s conditions!

At the rate we’re going, we’re going to run out of scenarios to play soon. Fortunately, Floodgate Games plans to have an app that generates more scenarios. It’s not released yet, so I haven’t been able to try it out, but that gives the game some longevity after you’ve played through the content in the envelopes. If your memory is bad, you may be able to play through scenarios again after some time, but some of the more unusual conditions in the harder scenarios might actually be easier to remember because they’re so bizarre.

As much as I like Décorum, I will note that it’s not for everyone. My wife told me it made her anxious just listening to us play the game, because although we were just playing into the characters, hearing people just say “I hate it” over and over without explaining why felt really stressful to her. My oldest daughter also struggled with the game—she’s somebody who likes to talk things out when there’s an issue, so the limited communication was not for her. (I suppose, upon reflection, it makes sense that my middle daughter loves it so much because she’s always been the kid who didn’t want to spell things out for anyone, leaving us to play a lot of guessing games about what she wanted or why she was upset.) And, of course, for those who don’t enjoy logic puzzles at all, this may end up being an exercise in frustration.

I’m guessing, though, that if you’re here reading a site called GeekDad, chances are good that you enjoy puzzles and figuring things out, and if that’s the case, I highly recommend giving Décorum a try. Just make sure you don’t throw out ghost mom’s lamp.

For more information or to order a copy, visit the Floodgate Games website.

Click here to see all our tabletop game reviews.

![]() To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

Disclosure: GeekDad received a copy of this game for review purposes.

Click through to read all of "Everyone Needs a Bit of ‘Décorum’" at GeekDad.If you value content from GeekDad, please support us via Patreon or use this link to shop at Amazon. Thanks!