Okay, here comes our waiter. I stare at the silverware. He clicks his pen. I’m always the last to order. Sometimes my mom tries to help me by tossing out what she thinks I want.

“Cheeseburger, John?”

“... Yyyy-uhh ... yyyueaah,” I force out.

If I’m lucky, there are no follow-up questions. I’m rarely lucky.

“And how would you like that cooked?” the waiter asks.

“... ... ... ... Mmm-muh ... mmm-edium.”

His face changes. I want it medium rare, but R’s are hard, so I cut myself off.

“And what kind of cheese?”

Vowels are supposed to be easier, but I can never get through that first sound. I skip it altogether and go right for the consonant.

“... Mmmmmuh ... ... muhm-merican.”

Now our waiter understands that something is wrong. He shoots a nervous glance at my mom, who fires back a strained smile: Everything is fine. My son is fine.

“Okay, next question,” he says with stilted laughter. “Curly fries or regular?”

I want regular, but remember, R’s are hard. Unfortunately C’s are hard too. I’m trapped. I try a last-second word switch. Bad idea.

“... Eeeeeeee-uh ... eeee-uh ... ... eeee-uh, eei-ther.”

I close my menu and push it forward.

“And to drink?”

Nearly every decision in my life has been shaped by my struggle to speak. I’ve slinked away to the men’s room rather than say my name during introductions. I’ve stayed home to eat silently in front of the TV rather than struggle for a brief moment at a restaurant. I’ve let the house phone, and my cellphone, and my work phone ring and ring and ring rather than pick up to say hello.

“... Huh ... huh ... huh ...”

I can never get through the H.

I understand that my stutter may make you cringe, laugh, recoil. I know my stutter can feel like a waste of time—of yours, of mine—and that it has the power to embarrass both of us. And I’ve begun to realize that the only way to understand its power is to talk about it.

When I was first diagnosed with a speech impediment, in the fall of 1992, stuttering was viewed as something to be fixed, solved, cured—and fast!—before it’s too late. You don’t want your kid to grow up to be a stutterer.

[Read: An ‘absolute explosion’ of stuttering breakthroughs]

Few experts can even agree on the core stuttering “problem”—or how to effectively treat it, or how much to emphasize self-acceptance. Only since the turn of the millennium have scientists understood stuttering as a neurological disorder. But the research is still a bit of a mess. Some people will tell you that stuttering has to do with the language element of speech (turning our thoughts into words), while others believe that it’s more of a motor-control issue (telling our muscles how to form the sounds that make up those words).

Five to 10 percent of all kids exhibit some form of disfluency. Many, like me, start to stutter between the ages of 2 and 5. For at least 75 percent of these kids, the issue won’t follow them into adulthood. But if you still stutter at age 10, you’re likely to stutter to some extent for the rest of your life.

Stuttering is really an umbrella term used to describe a variety of hindrances in the course of saying a sentence. You probably know the classic stutter, that rapid-fire repetition: I have a st-st-st-st-stutter. But a stutter can also manifest as an unintended prolongation in the middle of a word: Do you want to go to the moooooo-ooo-oovies? Blocks are harder to explain.

Blocking on a word yields a heavy, all-encompassing silence. Dead air on the radio. You push at the first letter with everything you have, but seconds tick by and you can’t produce a sound. Some blocks can go on for a minute or more. A bad block can make you feel like you’re going to pass out. Blocking is like trying to push two positively charged magnets together: You get close, really close, and you think they’re about to finally touch, but they never do. An immense pressure builds inside your chest. You gasp for air and start again. Remember: This is just one word. You may block on the next word too.

Stuttering is partly a hereditary phenomenon. A little over a decade ago, the geneticist Dennis Drayna identified three gene mutations related to stuttered speech. We now know there are at least four “stuttering genes,” and more are likely to emerge in the coming years. But even the genetic aspect is murky: Stuttering isn’t passed down from parent to offspring in a clear dominant or recessive pattern. Even when it comes to identical twins, only one of them might stutter.

The average speech-language pathologist, or SLP, is taught to treat multiple disorders, including enunciation challenges (think of someone who has trouble articulating an R sound) and swallowing issues. Yet many therapists are ill-equipped to handle a multilayered problem like stuttering. Of the roughly 150,000 SLPs in the United States, fewer than 150 are board-certified stuttering specialists. Even today, the medical community is divided over how to effectively help a person with a stutter. Many teachers don’t know how to deal with it either. It’s lonely. We’re told that 3 million Americans talk this way, but it doesn’t feel that common. You may have a sister or dad or grandparent who stutters, but in most cases, there’s only one kid in class who stutters: you.

My kindergarten teacher, Ms. Bickford, was the first person to notice an issue with my speech. One afternoon she brought it up with my mom, who called our pediatrician, who referred her to a speech pathologist, who determined that I indeed had a problem but couldn’t offer much in the way of help. We waited for a while, hoping it would get better on its own. It got worse. My next option was to see the multipurpose therapist in the little room at school.

I attended a Catholic elementary school in Washington, D.C. My parents could afford it only because my mom cut a deal with the principal: She’d volunteer as the substitute nurse in exchange for discounted tuition. On the days she showed up at school for duty, I’d head to the nurse’s office in the basement and eat lunch with her on a laminated placemat. I loved those afternoons. But to get down there to see her, I had to walk past the little room. I hated that room. Every time I entered that room, I felt like a failure.

There’s the knock. Kids stare as I stand to leave class. I walk down two flights of slate steps, turn the corner, and enter the little room. Everything in the little room is little: little table, little chair, little bookshelf. The decor is infantilizing. I’ve always been tall and gangly. At 7, my knees barely fit under the table. Most little rooms are peppered with the same five or 10 motivational posters: neon block letters, emphatic italics, maybe an iceberg or some other visual metaphor to explain your complex existence. This little room has a strange brown carpet that I stare into when the school therapist brings up my problem. She’s careful never to use the word stutter.

Okay, let’s start from the beginning.

There’s a stack of books on the table that are meant for people younger than me. Most sentences in these books are composed of one-syllable words. The vowels on the page are emphasized—underlined or in bold—a visual cue for me to stretch out that sound. Today we’re going to practice reading “car as “cuuuuhhhh-aaarrr.” This is embarrassing. I know what car sounds like. I know how other people say car. Doing this exercise makes me feel like an idiot; not only do I have trouble speaking, but now it seems like I can’t read. Every time I block on the C, I sense a pinch of frustration from across the table. But maybe I’m imagining it. After enough attempts, I can read one whole sentence in a breathy, robotic monotone.

“Thuuuhhhh cuuuuhhhh-aaarrrr drooooove faaaaaaast dowwwwwn thuuuuhhhhh rrroooaaaad.”

For some reason, this way of speaking is considered a monumental success. I think the way I just read that is more embarrassing than my stutter. But I have to keep doing it, because it’s the Big Rule: Take your time.

[Read: Doctors are failing patients with disabilities]

Have you ever told someone who stutters to take their time? Next time you see them, ask how take your time feels. Take your time is a polite and loaded alternative to what you really mean, which is Please stop stuttering. Yet a distressing amount of speech therapy boils down to those three words.

In his influential 1956 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, the sociologist Erving Goffman argued that in every social interaction, we are playing a part on an invisible stage. We want people to like us, to believe in us—no one wants to be labeled a fraud. Each time we speak, we may earn someone’s respect or lose it. We go to great lengths to sound smart, because we know that strong communicators are deemed worthy of esteem. Alex Trebek’s peerless ability to enunciate phrases during his 37-year run on Jeopardy transformed him into an icon. You can probably hear Trebek’s voice in your head right now: the clarity, the dignity, the confidence, the poise. America loved Trebek because, among other things, he was very good at saying words.

Stutterers, by contrast, are often portrayed in pop culture as idiots, or liars, or simply incompetent. In the 1992 comedy My Cousin Vinny, people wince as the stuttering public defender blocks horribly throughout his opening statement. One juror’s jaw drops in shock. (Austin Pendleton, a stuttering actor, played the part to an almost vaudevillian degree—something he later regretted; he’s said the performance “haunts” him.) In Michael Bay’s 2001 soapy blockbuster, Pearl Harbor, crucial seconds are wasted on the morning of December 7, 1941, because Red, a soldier who stutters, can’t speak under pressure. Red stumbles around the barracks gritting his teeth, trying to force out the news: “The JJJJ-JJJaps are here!” He eventually says it, but it’s too late: Enemy gunfire pierces the room where his friends are sleeping. Thanks to Red and his stupid stutter, more people than necessary have now died at Pearl Harbor.

A person who stutters spends their life racing against an internal clock.

How long have I been talking?

How long do I have until this person walks away?

When you’re a kid, there’s a quieter, slower, more insidious ticking:

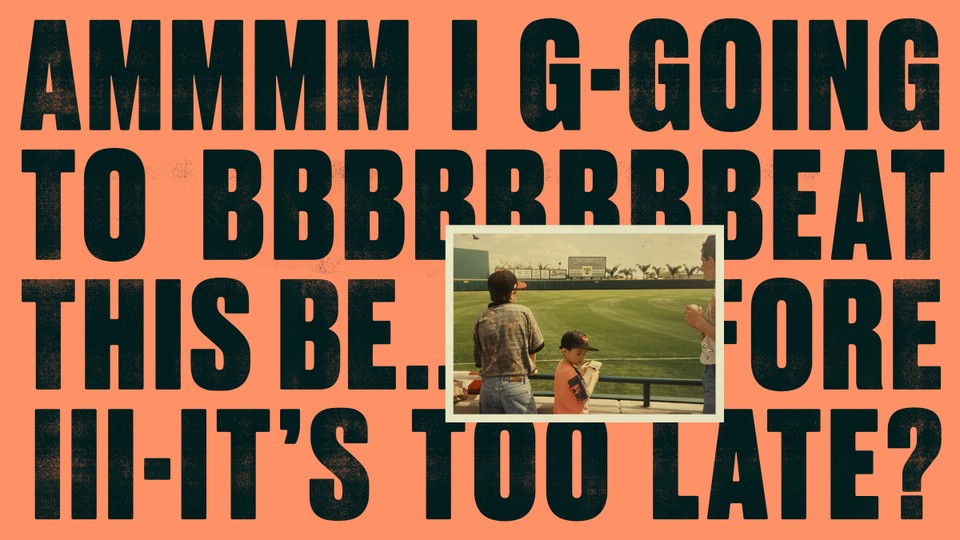

Am I going to beat this before it’s too late?

After I wrote about Joe Biden’s stutter in 2019, I began digging deeper into my own personal history with the disorder. One day I tracked down my second-grade teacher, Ms. Samson, and asked if she remembered anything about the way I spoke.

[From the January/February 2020 issue: Joe Biden’s stutter, and mine]

“I love the fact that you’re writing about this and putting it out there, because, gosh, from a teacher’s point of view, there’s not a lot—I mean, I wasn’t trained …” She searched for the words. “I wasn’t told how to handle this.”

Back then, we didn’t have a cafeteria—we’d eat lunch in our classroom. Ms. Samson kept a little radio on the corner of her desk. At lunchtime, she’d tune in to WBIG Oldies 100, and the space in front of the whiteboard would become the second-grade dance floor. Each afternoon was like a kids’ wedding reception, and I couldn’t wait for it to start. I’d wolf down my turkey on white then push back my chair and dart to the front of the class. I knew that the station’s midday DJ, Kathy Whiteside, had queued up a total hit parade: the Four Tops, the Supremes, the Temptations, Sam and Dave. This was an ideal time to work on my Running Man, or to whip out an invisible towel and do the Twist.

When Ms. Samson cranked her radio, my shoulders dropped and my lungs felt full. We looked like doofuses up there in our khaki pants or plaid skirts, but we were a unit of doofuses. This has special meaning when you’re the class stutterer. An hour ago I was flustered and out of breath, pushing and pulling at a missing word, feeling that familiar sweat drip down the back of my neck. Now I’m just another kid doing the swim to “Under the Boardwalk.” One day I sashay over to Michelle B. We giggle at each other. A new song starts. Jackie Wilson’s voice lifts me higher and higher. Then the music stops and I crash back to Earth.

“Your face would turn blotchy. Really, really red,” Ms. Samson told me. “You would cut your comments short because it was just too much work, or you figured, I lost the audience. But your impulse to participate—that’s how I knew: He’s thinking. He’s thinking and he wants to talk. That was the hardest part.”

This is the tension that stutterers live with: Is it better for me to speak and potentially embarrass myself, or to shut down and say nothing at all? Neither approach yields happiness. As a young stutterer, you start to pick up little tricks to force out words. Specifically, you start moving other parts of your body when your speech breaks down.

I still do this, and I hate it. I don’t know why it works, but it does: When I’m caught on a word, I can get through a jammed sound much faster if I wiggle my right foot. Blocked on that B? Bounce your knee! Unfortunately these secondary behaviors quickly become muscle memory. Sometimes they morph into tics. They also have diminishing returns: A subtle rub of your hands in January won’t have the same conquering effect on a block in February. So that means you’re stuttering for seconds at a time and moving other parts of your body like a weirdo. It’s exhausting. The curse of these secondary behaviors is that they can be just as uncomfortable as your stutter.

Eventually, I stopped going to the little room and began seeing a new speech therapist once a week at a clinic after school. Every Wednesday, Dr. Tom would bound into the waiting room and greet me with a high five. He grew up in a big Mississippi family and spoke with a warm country drawl. He oozed patience.

This arrangement was immediately better: no more leaving class, no more kids’ books. Dr. Tom’s philosophy was to pair fluency-shaping strategies with things I’d encounter in my daily life, like board games. We tore through hours of Trouble, pressing down on the translucent dome to make the imprisoned die pop. As I moved my blue men around the board, I’d practice techniques to try to smooth out my speech. If we read passages out loud, we’d use my actual homework.

Dr. Tom’s go-to technique was a popular strategy called “easy onset.” It’s a spiritual cousin to “cuuuuhhhh-aaarrr,” but with more emphasis on the first sound of a word. The objective is to ease into the opening letter with a light touch, stretch the vowel, then shorten your exaggeration over time. No two stutterers struggle with the same collection of sounds, but every stutterer is haunted by specific vowels and consonant clusters. Many who stutter come to dread the act of saying their own name. People say their names more frequently than any other proper noun, after all, and stutterers tend to be extra disfluent when we meet new people.

My jaw locks when I go to form the J in John. I typically enter a long, painful block, then bark out the word at full volume: … … … … … … … … JOHN! Sometimes my J manifests as a rapid repetition, like a machine gun, or a Buick that won’t start: Jjjjjjjjjjjjjjohn. I’ve wasted whole afternoons fantasizing about what life might be like with another name. Why didn’t my parents choose Michael? All I’d have to do is thread that M to the I. The second syllable plops out, like a raindrop on a creek. Michael. I’ve said Michael so many times that it’s lost all meaning: Michael, Michael, Miiiichael. (Of course, if I were Michael, I’d probably block on the M.)

Stuttering is an invisible disability until the moment it manifests. To stutter is to make hundreds of awful first impressions. And an awkward exchange between two people affects not just the person being awkward, but the person forced to deal with said awkwardness. A stutterer may enter a room full of “normal” people and temporarily pass as a fellow “normal,” but the moment they open their mouth—the second that jagged speech hits another set of eyes and ears—it’s over. As Erving Goffman notes: “At such moments the individual whose presentation has been discredited may feel ashamed while the others present may feel hostile, and all the participants may come to feel ill at ease, nonplussed, out of countenance, embarrassed, experiencing the kind of anomy that is generated when the minute social system of face-to-face interaction breaks down.”

One phrase leaps out at me there: “may feel ashamed.” This assumes that the shame will pass. I wish I could pinpoint the moment when shame changed from something that periodically washed over me to something I began lugging around every day like a backpack.

Some days Dr. Tom and I would sit on the floor in front of a big mirror and study the movements of our mouths. This was harder than it sounds. The mirror ran the length of the wall, and there was nowhere else to look: I had to watch myself stutter. One day I sat close enough, with my eyes just a few inches away from the surface, that I could make out shadowy figures in a dark room on the other side of it. Discovering this was a little like learning the truth about Santa Claus: You mean everyone knows but me? There was a hidden microphone somewhere in our room. The space on the other side had little speakers to transmit our voices. (You’ve seen this on a million cop shows.) I asked Dr. Tom who was in there watching us, and he told me: Occasionally, graduate students observed our sessions, and that was a good thing, because we were teaching them how to be therapists themselves. Other days, the shadowy figure was my mom.

I don’t blame her for watching. That’s what the doctors told her to do. I have sympathy for the parents of children who stutter. You want nothing more than for your kid to live a happy and successful life, and this new thing, this ugly problem, seems to threaten that. There’s also the aforementioned race against time: With each passing year, true fluency becomes harder to attain. Many health insurers don’t cover speech therapy, preventing people with limited funds from having the chance to work with experts. And yet, even many parents who have the means—those who dutifully shuttle their kids to appointments—leave with flawed advice:

Remind them to use their techniques! Tell them to take their time!

We stutterers anticipate our blocks well before they occur. We know how our brains and lungs and lips confront every letter of the alphabet. We know what we look like, what we sound like, what we make shared spaces feel like. We know that our stutter hasn’t gotten better, and that maybe it’s getting worse. We sense that most nights you, Mom and Dad, pray for it to go away. We know you believe you’re helping. We don’t know how else to tell you this: You’re not.

When a person of authority tells a young stutterer to “use your techniques,” they are confirming the stutterer’s worst fear: No one is listening to what you say, only how you say it. Enough of this makes you not want to talk at all. Fluency techniques may work in a therapy room, but, in most cases, they’re extremely hard to deploy in the real world. Speaking like a robot is not natural.

[Read: Learning to love stuttering]

“I could see you using strategies—you were doing things with your breath,” Ms. Samson told me. “And probably you had practiced whatever it was so much, and just couldn’t live up to what you knew you could do. I could see the defeat. You would put your head down and sort of walk back to your desk.”

What would it take for me to let go of that feeling? More than two decades later, I finally had a glimpse of an answer. If I was going to make peace with the shame of stuttering, I’d have to abandon the illusion that natural fluency might one day come, that my “two voices” would magically merge. I’ll always have a voice in my head that reads this sentence, and a much different voice that reads it out loud. I don’t like that fact about myself. But I don’t have to keep fighting it.

This article has been adapted from John Hendrickson’s forthcoming book, Life on Delay: Making Peace With a Stutter.